Charley Patton's "Some of These Days I'll Be Gone"

What music is white and what music is black?

Charlie Patton: Father of the Delta Blues

I’ve been listening to Charley Patton’s discography for my thesis. He’s the grand old ancestor of the blues — you could argue that title belongs to Blind Lemon Jefferson, whose six-figure sales led Paramount Records to record more blues artists — but because of Blind Lemon’s success (his records were easy to come by), he was an afterthought for the wealthy, white, male record collectors of the late ‘50s who are uniquely responsible for the survival and intrigue of the Delta blues.

I don’t know who said it, it might have been Elijah Wald, but I read somewhere that perhaps all the hype around Patton has to do in part with the fact that his records are the worst recorded, that you have to suffer through so much static just to hear him play. By the time Robert Johnson records in the mid ‘30s, the difference in audio quality is substantial. Still, though, I find Patton singular in his mischievousness — he had a reputation for being a rabble-rouser — and it’s this quality I enjoy most in his music. Like on “Shake It Break It,” a song about encouraging his ‘rider’ to, more or less, ‘throw that ass in a circle,’ as he repeats the titular declaration that sounds like it could’ve been pulled from an Outkast song.

Working through all of Patton’s sides, I was jostled out of my crackle-induced haze by “Some of These Days I’ll Be Gone.” Nothing like Patton’s signature blues. I figured he hadn’t written it. Quick google search: made famous by Sophie Tucker (white and Jewish) in 1910, and written by the African American composer Shelton Brooks.

Here, back to back, Patton’s version and Tucker’s.

“Some of These Days” — A Racial Node

The legend goes that Mollie Elkins, an African American dancer working for Tucker, introduced her to the budding black composer Shelton Brooks. At first, Tucker resisted, shrugging off the mostly unknown Brooks. But Elkins persistence led Tucker to listen to “Some of These Days,” which she immediately took to. In her autobiography, Tucker writes that she “could have kicked [herself] for almost losing it. A song like that!” all because the composer was black. She goes on to compare the tune to the work of Stephen Foster, the famous minstrel composer.

A famous white performer finds a hit song, which she almost ignores because it was written by a black man. Following? Well, it got stranger as I dug into Tucker’s persona. Nickname: “The Jewish girl with a colored voice.” Tucker didn’t just sound African American, she and her record label presented her as such. Here she is in blackface.

Tucker eventually put down the cork, but when she toured Europe, audiences puzzled over this singer they always believed to be black.

The racial back-and-forth of “Some of These Days” continued in the public imagination. In his novel Nausea, French existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre makes the song something like a catch phrase for his angst-ridden protagonist Roquentin. Yet Roquentin, or Sartre, or both, mix up the racial dynamic of the track, asserting a black singer and Jewish songwriter.

White & Black in the Delta

What to make of all the confusion? I don’t know. Music, especially American music, constantly bounces between black and white, with the latter often expropriating the former. When I finally returned to Patton, I found that his own racial identity, and that of the musical genre inextricably linked to his name, proved equally unstable.

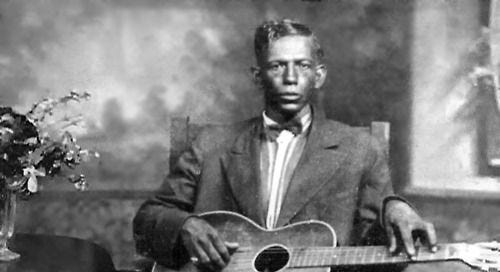

Patton defies the folk revival’s expectations for the archetypal bluesman. A quarter Native American, a quarter white, and half black, the single surviving photo of him is distinctly mixed-race. Patton’s father’s successful businesses made the family one of the wealthiest in the area, and the Pattons maintained close ties with the Dockery family, owners of the Dockery Plantation to which they moved in 1900.

Strange, The Father of the Delta Blues singing “Some of These Days,” a Tin Pan Alley tune — but really only strange from my perspective. Why wouldn’t Patton sing a pop song, a song familiar to a wide audience? After all, blues musicians developed repositories of songs across genres; they’d entertain dusk-til-dawn and were expected to keep things fresh. And Patton, more than most of his contemporaries, was as sought after by white audiences as black ones.

Patton’s nephew Tom Cannon recalled that Charley played more white parties than black juke joints — probably because they paid better. So in demand was Patton that he often booked multiple gigs on the same night, never wanting to say no. This led to conflicting engagements, conflicts that often occurred across racial lines. The scheduling conflicts were no laughing matter. Patton’s niece recalled an instance in which a white man, wielding a gun, came to where Charley was performing for a black audience and insisted that Patton leave the current party to come perform at his own:

A man come out there and shouted right straight up, “Charley, come on out of there.” My husband said, “You gonna have to stop playing music. These folks gonna kill you.” Us runned, and I losed one of my shoes. My husband had to go back and get it the next morning. I wasn’t but fifteen years old. . . . And Uncle Charley sat on that bridge and played for them white folks until about five o’clock the next morning. All them white folks was all on that bridge dancing. Uncle Charley was sitting there making music for them. They done broke up this other dance, and then they put their dance on the bridge . . . I’ll never forget that.

When performing for white people, Patton would often mix up his set list, opting for more love songs and fewer blues. The same niece remembered a particular favorite amongst whites. She couldn’t remember the name, but it had the lyrics “I’ll miss you, honey, when you’re gone.” And which song is that? “Some of These Days.”

PS

For some reason, the last email didn’t send to any Dartmouth addresses. So, here.

Ethan, thank you for sharing this post. I am interested to know more about Sophie Tucker’s anti-black racism — you mentioned twice that she almost passed over Some of The Days on account of the composer’s race. How does her racism play a role in her career as a black-faced performer, singing black music & dancing alongside black dancers? Thanks