Lead Belly: Whose Myth?

The forgotten and forbidden book detailing John Lomax and Huddie Ledbetter.

I return to Lead Belly and John Lomax. These two men initiated the folk revival’s influence on popular culture. Just look at The Weavers: they took “Goodnight, Irene” to #1 in 1950, and “Kisses Sweeter than Wine” — the tune taken from Lead Belly’s “If It Wasn’t for Dicky” — rose to #19 the following year.

But the best argument for Lead Belly’s influence on pop culture comes from none other than George Harrison:

No Lead Belly, no Lonnie Donegan. Therefore no Lead Belly, no Beatles

Donegan ushered in the skiffle craze with his cover of “Rock Island Line,” which inspired 16-year old John Lennon to form The Quarrymen, a group that soon included Paul McCartney and George Harrison.

Forbidden or Forgotten?

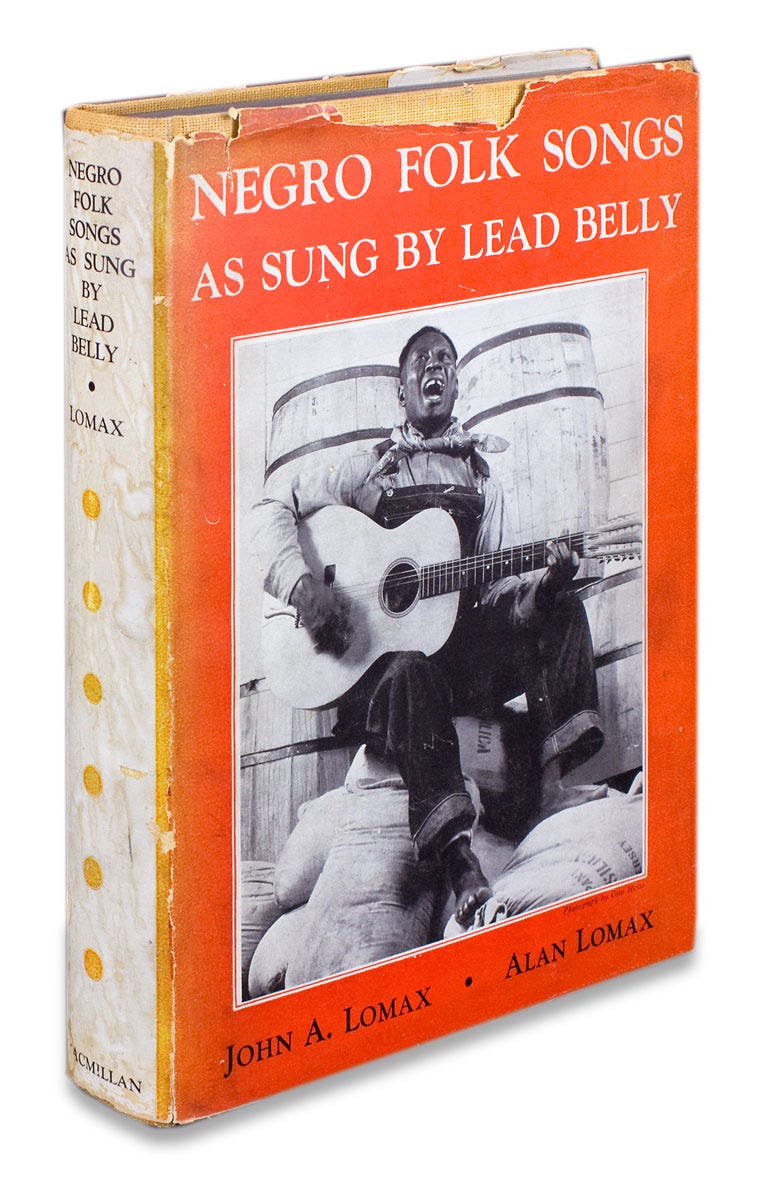

In 1936, one year after his relationship with Lead Belly spoiled permanently, John Lomax published Negro Folk Songs As Sung by Lead Belly. The book is hard to find; with only one edition ever printed, copies regularly fetch $500. Luckily, I got my hands on one through UNC’s library. And Lead Belly’s scarcity started making a lot of sense…

John Lomax’s racism is not new news, nor has it been forgotten to history; John Szwed’s 2011 biography of Alan Lomax paints an unsparing portrait of Alan’s father. What makes Lead Belly so interesting is that both men — John Lomax and Huddie Ledbetter — speak for themselves. Lead Belly tells his own story in unsavory terms, painting himself as a rockstar playboy. I want to summarize the 60 page backstory that opens the book, highlighting those elements that have gone unmentioned in recent scholarship and journalism.

Lead Belly’s Oral History, Lomax’s Memoir

Lomax’s goal appears twofold: to characterize Lead Belly as an animalistic sexual deviant prowling the world for women to fuck and men to kill, and to cast Lead Belly as a relic of a lost agrarian past, mostly untouched by but not above the poison of pop songs and jazz.

Lead Belly, born 1885, in his early years escaped the influence of jazz, though his inheritance was rich from the Negro minstrel class. Even the “blues” came later. Living in the country, he first learned simple tunes set to stories about taking water to thirsty plowmen, of picking cotton, of shooting a goose flying South—songs dealing with nature, sung by men at work in the fields.

He … had a career of violence the record of which is a black epic of horrifics.

We present this singer, not as a folk singer handing on a tradition faithfully, but as a folk artist who contributes to the tradition, and as a musician of a sort important to the growth of American popular music.

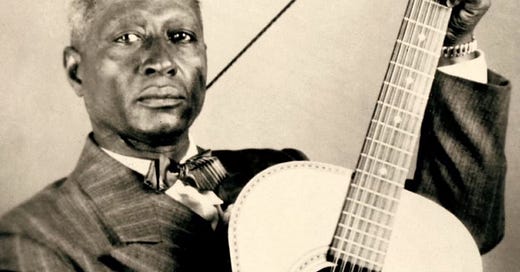

Ledbetter, for his part, leans into a sort of self-mythologizing, proudly reveling in his self-proclaimed title, “The King of the Twelve-String Guitar Players.” By age 16, he had two kids and played guitar at parties in Texas. As an only child, his parent’s spoiled him:

Wasn’t nothin’ my mamma an’ papa wouldn’ do for me, wasn’ nothin’ dey wouldn’t buy me, if I wanted it. When I got ‘bout fifteen years ol’ an’ ‘gin to go ‘round’ to de suckey-jumps an’ what you call breakdowns in de bottom, my papa bought me a Puttection Special Colt fit under my coat in a scabbid. He tol’ me, says, “Now, son, don’ you bodder nobody, don’ make no trouble; but if somebody try to meddle wid you, I want you to puttect yo’se’f.” He bought me a bran-new hoss an’ saddle, too—you know, hosses was in style den, jus’ like late-model cars is now—an’ you know I felt mighty proud ridin’ down de road on my bran-new hoss wid my new saddle screakin’ so ev’ybody could know, an’ my pistol in its scabbid under my arm. I felt like a man, sho’ ‘nough.

His Protection Special Colt, his sexual precocity, his swaggering mannishness, even the songs he sang, suggested Shreveport and the red-light district.

Lomax loves harking on Lead Belly’s sexual exploits, but in all fairness, Lead Belly himself seems to enjoy the same.

Lead Belly’s attitude toward women had become completely arrogant and domineering. He kept one at home to clean his house and give him comfort when the world turned sour on him, and he believed that all other women belonged to him by rights. The truculent Dallas prostitutes had nearly chopped his head off because of his swaggering.

The blood ran warm in his veins. The excitement of Dallas and the fast Dallas women, the “noted riders,” made him restless. He rambled, and his desire for women increased. He sang about them; his body, sucking up strength from the ground, demanded them, and he needed more and more to reassure himself.

All these attempts at making Lead Belly ‘primitive’, his sexuality summoned from the soil, his actions governed by instinct, they’re gratuitous and gross. They begin to characterize Ledbetter as a criminal. He had, lest we forget, killed multiple men, maimed others, and beat women who refused to sleep with him; read Lead Belly, and he’ll tell you all this himself. One ought to remain skeptical though of even the words that appear to come from Lead Belly’s mouth; Lomax surely took liberties while editing.

The Prison Years

Lead Belly first served time for murder, a 30-year sentence. He paints himself as a John Henry-type figure: the fastest cotton picker, the best with a hoe on the whole chain gang.

The central Lead Belly myth is as jaw-dropping as its mythologized form. When Texas Governor Pat Neff visited the Sugar Land prison, Lead Belly entertained him, his wife, and guests, improvising a song pleading for his pardon. Neff told Lead Belly he’d pardon him before he left office, and sure enough, Lead Belly was one of only five convicts Neff pardoned.

(Lead Belly went by the alias Walter Boyd while in prison):

Dat man [Neff] sho was crazy ‘bout my singin’ an’dancin’. Ev’y time I’d sing a new song or cut a few steps he’d roll me a bran-new silver dollar ‘cross the flo’. Las’ song I sung was a song I had made up askin’ him to turn me loose, let me go home to Mary. (I called her my wife, if she wasn’ my wife.) He tol’ me when I was through, say, “Walter, I’m gonna give you a pardon, but I ain’ gonna give it to you now. I’m gonna keep you down here to play for me when I come, but when I go out of office I’m gonna turn you loose if it’s de las’ thing in de worl’ I ever do.”

After 6.5 years, Lead Belly was free. He would return to prison, escape, return, and meet the Lomaxes in the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola.

Lead Belly and Lomax Tour Prisons, Colleges

Free from prison, Ledbetter worked for John Lomax — not just as a traveling musician and prison-inmate interlocutor, but also as a servant, a “body servant” in Lomax’s words. And John liked the one-on-one attention, Lead Belly jostling him awake in the morning with a fresh cup of coffee, a warm bath running in the room over.

Together, the two men recorded folk songs at prisons across the south. From their excursions:

At one penitentiary, where echoes interfered, we were offered the soundproof execution room, which contained as its sole piece of furniture the grim electric chair, the “hot seat,” covered with a white sheet.

Lead Belly grew frustrated with Lomax, who only cared for black people when they were behind bars:

He often said: “I’m tired of lookin’ at black folk in the penitenshuh. I wish we could go somewheres else.” In such a mood he was neither companionable nor helpful.

By the time Lomax and Ledbetter started touring colleges, Lead Belly had had enough. He spent nights in black neighborhoods singing and drinking, even running into Cab Calloway in a Harlem bar. Lomax did not like this:

The blame would be rightly laid at my door should Lead Belly in his wild night life kill some one. What excuse could I make for turning such a man loose in a city? I was filled with terror at my position and responsibility.

When the tour came to a close, Lead Belly reconvened with his wife Martha at the Lomax house in Wilton, CT. Tensions grew as he failed to conform to John’s idealized model of the jailbird songster.

Lead Belly would perhaps have been happier had more physical labor been given him. He had no lazy atom in his make-up.

Soon, even Lomax was forced to realize his understanding of Lead Belly was built atop projection. He imagined a life for Ledbetter and Martha in some bayou backwoods, once again removed from the corrupting influence of consumerism.

My dream of setting up him and Martha on a farm stocked with cattle, pigs, chickens, etc., … was only a dream. It was I who wanted the pretty home for them, not Lead Belly and perhaps not Martha. What they planned first was a big, shiny automobile, lots of flashy clothes.

Fed up with John’s demands and ridicule, Lead Belly ditched Wilton and returned to Shreveport, Louisiana.

Reading Negro Folk Songs As Sung by Lead Belly, you encounter a myth being made in real time. This is a narrative that would be repeated throughout the blues revival — the outlaw bluesman, a pugnacious womanizer, habitual drinker, and unmatched entertainer. Yet Lomax allows just enough of Lead Belly’s voice for the fiction of the myth to live on the page, whether in Lomax’s projections, or Lead Belly’s exaggerations. The book deserves a second printing, one bookended with essays by current authors interested in folk music. It’s been 85 years.