John Fahey: an iconoclastic guitarist, a scathing critic of the folk revival, a surrealistic author. The man is many things, but no one would call him a singer. Which is not to say he never sang. One example that comes to mind is “Je Ne Me Suis Reveillais Matin Pas En May,” which translates to I did not wake up on that day in May, or I woke up this morning, not in May. Whatever it is, in poorly rendered French. Spotify, Apple Music.

Shouting in drunken, garbled, not-English and not-French, Fahey strums simple chords. This is coffeehouse cliché, C-F-G, music even I can play. He sounds bad. Both the guitar and vocals, but especially the vocals. A few laughs and snippets of conversation peek out of the recording, like we’re really in a coffee shop. A whiny head-voice, atonal gravel, the full spectrum of poor singing. Fahey sells his vocals in all faux-sincerity. Wailing, reaching, missing. A harmonica. It’s Fahey’s dig at the main stream of the folk scene, but mostly at Dylan. Trying to say so much and instead saying nothing at all, sounding grating while doing it. French, the language of pretension. High and mighty idealists with their simple musical tradition ill-fit for lofty political goals. Not just ill-fit—there’s something sacrilegious, Fahey says, a fatal misreading.

Before Blind Joe Death, there was Blind Thomas

A quick initiation for the unfamiliar. Fahey invents a mythical bluesman—Blind Joe Death—who, according to the narrative, taught Fahey everything he knows. The saga plays out in the liner notes of Fahey’s first four LPs: Blind Joe Death (1959, half of which is credited to Death himself), Death Chants, Breakdowns & Military Waltzes (1963), The Dance of Death & Other Plantation Favorites (1964), and The Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death (1965).

But before Fahey invented Blind Joe Death, before he settled on instrumental blues/folk/American Primitive/whatever you want to call it, he had another alter-ego, Blind Thomas, and unlike the later incarnations, Thomas spoke.

Thomas didn’t come to light until 2011 with the release of Your Past Comes Back to Haunt You, a collection of Fahey’s earliest recordings stretching back to 1958. The compilation is a must for any Fahey devotee. It’s filled with rough versions of later staples like “Brenda’s Blues” and “The Transcendental Waterfall.” But I want to talk about the tracks credited to Blind Thomas, the tracks on which Fahey sings—if you can call it singing.

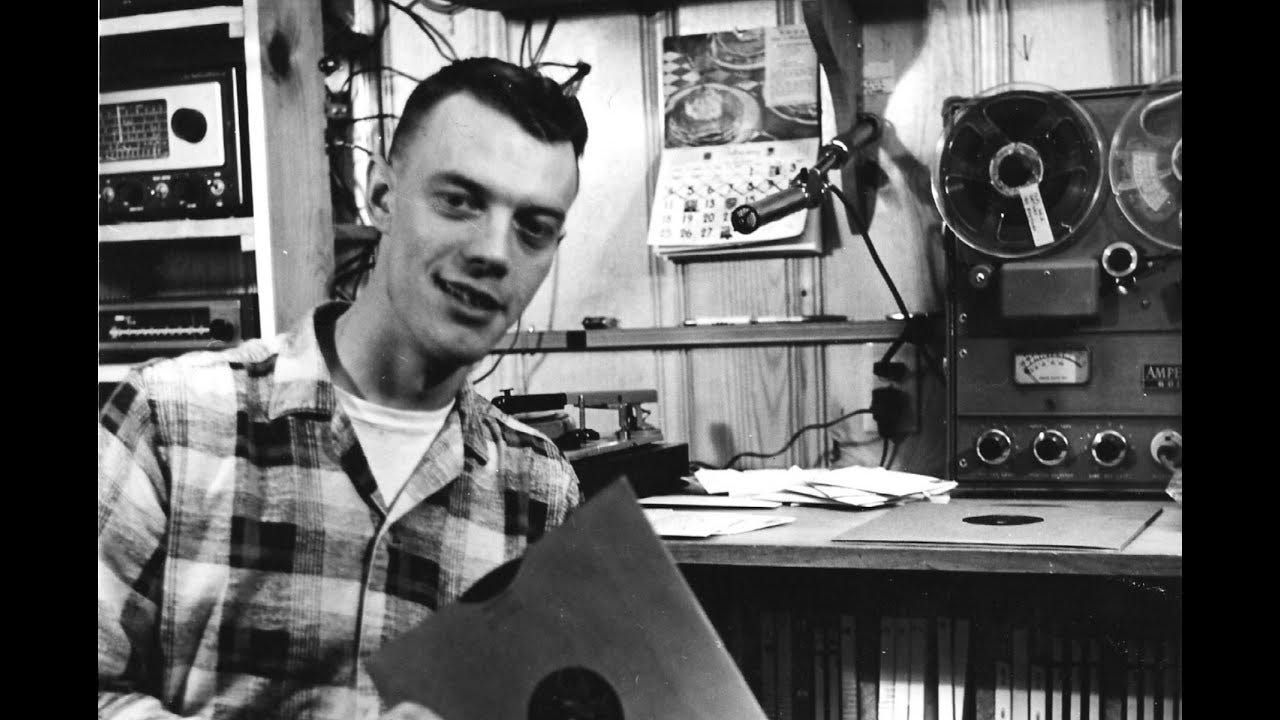

As the story goes, Joe Bussard, a fellow 78 collector who lived near Fahey in the DMV, would invite Fahey over, pump him full of booze, and insist Fahey impersonate the delta bluesman both collectors loved so much. Bussard owned the equipment necessary to cut 78s on the spot, and that’s just what he did, paying Fahey for his trouble.

Fahey is audibly fucked up on these recordings. He deepens his voice, growling. It’s noticeably affected. These songs aren’t remarkable as music. What’s interesting to me, though, is what they reveal about what Fahey’s thinking. Over the course of the multi-part Blind Thomas Blues, he name-checks his philosophical influences: Sartre, Kierkegaard, Dostoyevsky, Nietzsche, Schopenhauer. Existentialists. Sad boys. Angry incels. There’s “Dasein River Blues,” hid nod to Heidegger. Fahey would begin, but never finish, a philosophy P.h.D at Berkeley in the mid ‘60s. “Everybody’s in nothingness now,” he spits at the end of Part 1, a wry nod to Sartre’s magnum opus. Spotify, Apple Music.

The other influence all over the Blind Thomas performances is Charley Patton. Fahey as Thomas does covers of “Banty Rooster Blues,” “You Gonna Miss Me” (remember this one from here?), and “Tom Rushen Blues”—of which Fahey is said to own the only existing copy. He also covers Patton’s spiritual, “Jesus Gonna Make Up My Dyin’ Bed,” which Fahey would later transform into one of his more famous compositions, “Requiem for John Hurt.” I like this version best, live in ‘68 on The Great Santa Barbara Oil Slick, but below, a live rendition from 1981. You ever see hair like that? What makes a man decide to present himself in such dereliction? Cool striped shirt, though.

Seeing his hair made me immediately want to stop listening to folk music. Wonder why he transitioned from Blind Thomas to Blind Joe Death.